The 7 Most Powerful Moats For AI Startups by YC

The full breakdown every AI founder and VC must know by heart and plan accordingly

Hey everybody, welcome back to The AI Opportunity.

For everyone bulding and investing in AI there’s one big question in their mind. How do we avoid getting killed by OpenAI?

Well, some partners of YC distilled down the 7 most powerful moats for AI startups.

So I thought it would be a good exercise to break them down.

This is a must know for every AI founder and VC out there, so let’s get to it!

0. The moat before all moats: speed

YC’s view is blunt:

At the very beginning, your only moat is speed.

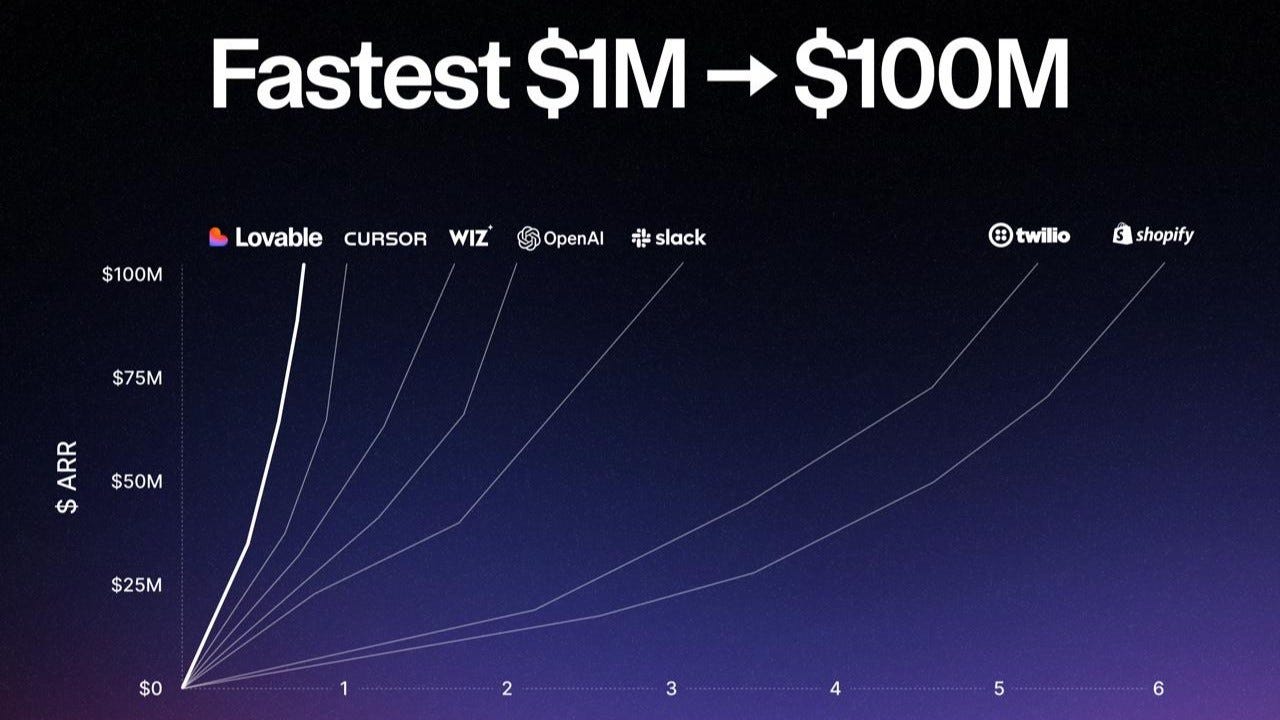

Cursor and Windsor are the canonical examples.

In the early days, Cursor ran one-day sprints. Every single day, the clock reset. Ship, ship, ship.

No big company can move like that. At Google or Anthropic, a feature needs PRDs, reviews, approvals, comms. Weeks or months, not days.

Same story with ChatGPT vs Google:

A tiny team inside OpenAI shipped the first version of ChatGPT in months.

Google had the talent, the research, and a head start with transformers — but also the weight of Search and the ad business. They couldn’t move.

This is the first big YC point:

Don’t reject a startup idea because you can’t see the moat yet.

If you don’t have anything to defend, you don’t need a moat. You need speed and a painful problem.

Find:

A person with a hair-on-fire pain (“I might get fired if this doesn’t get fixed”),

Build something that actually works for them,

Then worry about defense.

Everything below is “1 → 10 → 100 → 1,000” thinking — not “0 → 1” thinking.

The 7 canonical moats — updated for AI

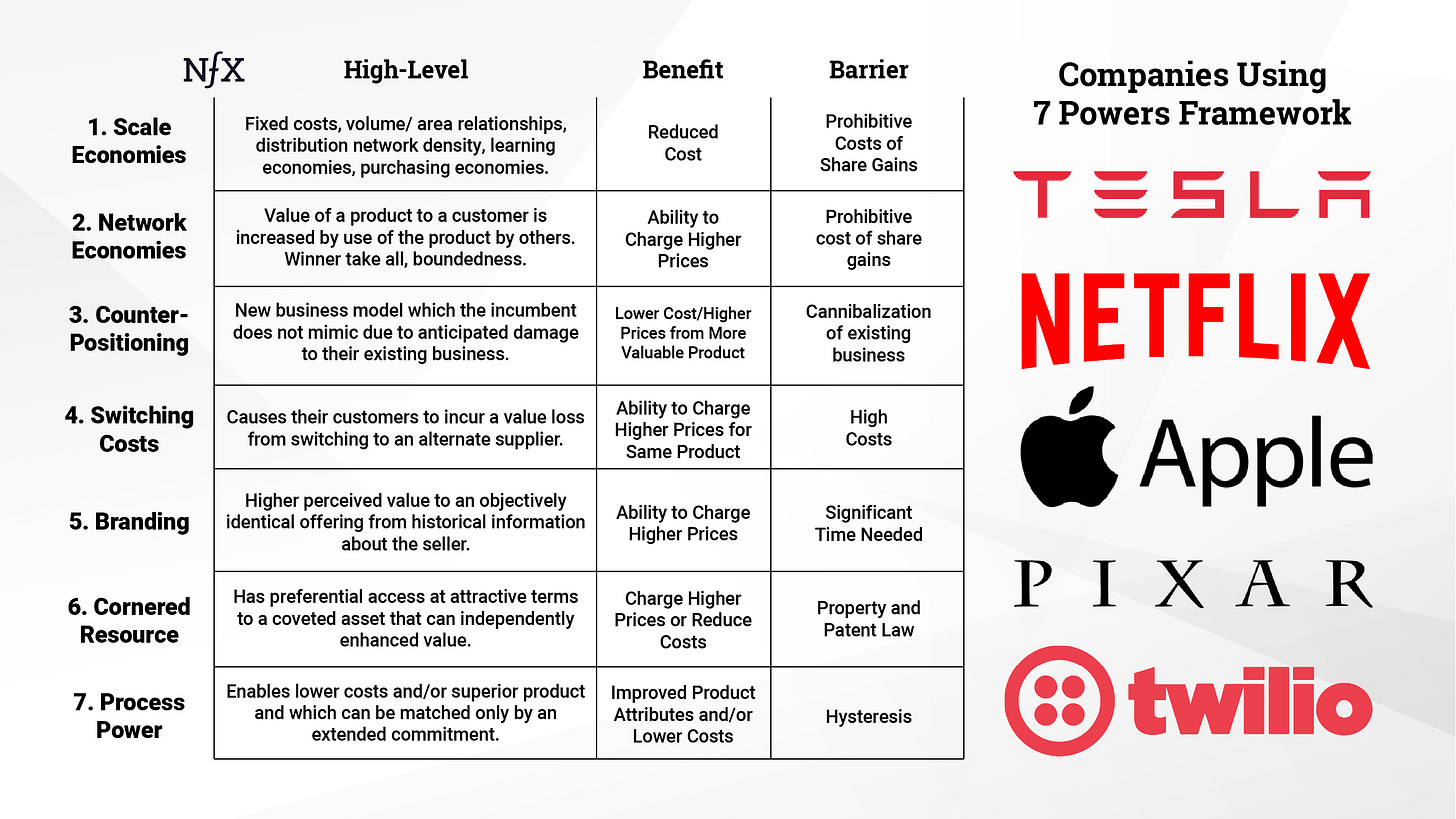

Hamilton Helmer’s book calls them “powers”. For AI, think of them as 7 categories of defensibility you can grow into:

Process power

Cornered resource

Switching costs

Counter-positioning

Brand

Network effects

Scale economies

YC’s update adds an eighth meta-moat: speed, which we just covered.

Let’s go one by one with the AI versions.

1. Process power: when the “boring” work is the moat

Definition (YC / Helmer version):

You’ve built a complex system — product + operations + workflows — that is very hard for others to replicate.

Classic example in the book: Toyota’s production system.

Modern SaaS examples: Stripe, Rippling, Gusto, Plaid.